What events led to the Battle of Little Bighorn?

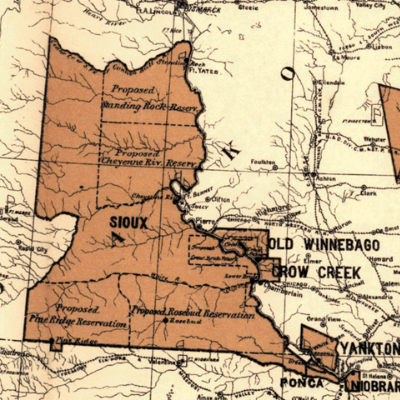

In 1868, many Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho tribal leaders agreed to sign the Treaty of Ft. Laramie. This treaty created a large reservation west of the Missouri River in the present state of South Dakota called the "Great Sioux Reserve." The tribes believed they would be left alone in peace, but the American government would respect the treaty for only a short time. By 1872 the area was being surveyed for a route for the Northern Pacific Railroad.

In 1874, tensions escalated when Colonel George A. Custer led an expedition to establish a fort in the Black Hills and discovered gold. By March 1876, prospectors were pouring into the Black Hills, with 11,000 white men gathered in Custer City. The U.S. tried negotiating with the Lakota to purchase the Black Hills, but the Lakota rejected the offer. The Black Hills are sacred to them. 1

The climax came in the winter of 1875 when the Commissioner of Indian Affairs issued an ultimatum requiring all tribes to report to a reservation by January 31st, 1876. The deadline came with no response from the Native Americans, and matters were handed to the military.

By June, the tribes had come together for a variety of reasons. The region containing the Powder, Rosebud, Bighorn, and Yellowstone rivers was a productive hunting ground. The tribes regularly gathered in large numbers during early summer to celebrate their annual sun dance ceremony. 1 During the ceremony, Sitting Bull received a vision of soldiers falling upside down into his village. He foretold there soon would be a great victory for his people. 1

What happened at the Battle of Little Bighorn?

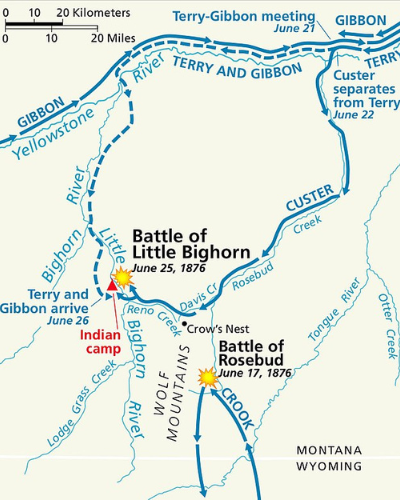

The non-compliant Native Americans were now deemed "hostile," and the military had to force the Native American warriors to comply. General Phillip Sheridan, commander of the Military Division of Missouri, created a strategy to send one column of soldiers with General George Crook from Ft. Fetterman northwest, one column with General Alfred Terry from Ft. Abraham Lincoln southwest, and the third column with General Gibbon from Ft. Ellis east.

Crook's force of 1,049 officers and men left Ft. Fetterman on May 29th and fought with Crazy Horse on June 17th in the battle of the Rosebud, which the warriors won.

Generals Terry and Gibbon met up at the mouth of the Rosebud River on June 21st. These two forces comprised 1,450 cavalry, infantry, and scouts. Terry sent Custer to scout up the Rosebud while taking steamers to ferry across Gibbon's force, which was to go up the Bighorn and meet with Custer.

On the morning of June 22nd, Custer set out with 850 men, Indian scouts, and guides up the Rosebud. Scouts reported seeing the Sioux camp, and the following day Custer himself was looking down on the encampment. By late morning Custer's troops moved down the western slope of the Wolf Mountains. He received a scouting report detailing the size and position of the Sioux encampment and moved his command down the valley.

Here Major Marcus Reno and Custer separated into two forces. Reno advanced down the left side of the valley. Custer's command moved down the right side and out on a rising plain. Reno's troops were still in full view of Custer. As Custer emerged from the valley, he lost sight of Reno for a few minutes and then came close to the crest of the hill overlooking the valley. Here he halted and sent scouts ahead. Receiving a signal from the scouts, Custer and his staff rode to the top of the summit. He traveled along the ridge for a time and then turned left down a dry creek called Medicine Tail Coulee. He rode out close to the river but did not cross. Custer now led his command back up the valley a short distance and turned left.

By now, the warriors knew where Custer's troops were and began crossing the river. Reno had by this time already fought with the warriors and retreated with his men onto the bluffs. The Sioux could give their full attention to Custer and his men. The Sioux attacked. Custer shot at the attackers, who were reckless enough to come within range, but the whole movement was a retreat. Whether or not Custer was planning to withdraw far enough from the river to make a stand or had started a retreat to the mountains is unknown. The Sioux thought he was trying to reach the mountains and headed him off. On June 25th, Custer's entire command was killed.

What was the aftermath?

Two days later, General Terry arrived with Gibbon's men and met with the remains of Reno's troops. They buried Custer's two hundred dead, gathered Reno's wounded and withdrew to the mouth of the Little Bighorn. Terry applied for reinforcements, but the groups of warriors had scattered, each following their leaders, some back to the reservations. The policy was now to disarm and dismount all of the Native Americans at the agencies.

Sitting Bull and Gall escaped into Canada. Crazy Horse remained with his followers in the Bighorn Mountains until the spring of 1877, when he surrendered. Crazy Horse remained at Ft Robinson under military watch. He died at the end of a soldier's bayonet there in September.4

Gall crossed the border back into the United States in 1881 and met with General Miles. After stubborn resistance, he surrendered. He lived peaceably on the Standing Rock agency until his death in 1894. Sitting Bull surrendered in 1881. In 1883 he was taken to the Standing Rock agency. During the Ghost Dance incident in 1890, when he was arrested, the great Sioux chief resisted and was killed.

The battle was a momentary victory for the Northern Plains tribes. Custer's Last Stand became a rallying point for the United States to increase its efforts to force native peoples onto reservation lands. Most of the declared "hostiles" had surrendered within one year of the fight, and the U.S. government took the Black Hills without compensation.

Decades later, on June 30, 1980, the Supreme Court ordered the U.S. to pay the Lakota over $105 million for the government's illegal seizure of the Black Hills a century earlier. The court ruled that the "nations" given to the Sioux when the government took the land were not "just compensation" for the 7.3 million gold-laden acres sacred to the Sioux. The land legally belonged to the Sioux under the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, which Congress approved before the discovery of gold in the area.2

The $103 million in trust continues to grow in value, but the Lakota have refused the money saying, "The Black Hills are not for sale.. One does not sell their holy land." 3

1 https://www.nps.gov/libi/learn/historyculture/battle-story.html

2 https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1980/07/01/sioux-win-105-million/a595cc88-36c6-49b9-be4f-6ea3c2a8fa06/

3 https://www.indianz.com/News/2020/07/06/tim-giago-the-black-hills-are-not-for-sa.asp

4 https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/native-history-crazy-horse-killed-by-us-soldier-while-in-custody

Share this page with a friend to help raise awareness of Native American history and culture.

Great Sioux Reservation. 1888 Map showing the location of the Indian reservations within the limits of the United States and territories, compiled from official and other authentic sources, under the direction of the Hon. Jno. H. Oberly, Commissioner of Indian Affairs; Wm. H. Rowe, draughtsman.

Little Bighorn battle map, zooming out to show the military movements leading to the decisive battle. Created by U.S. National Park Service.